Dan Timotin

Dan, who is supposed to be a mathematician, keeps trying to invent himself in alternate lives (in one of which he is a contributor to Aainanagar).

When we were told during the conference in Bangalore that there is a nice terrace above the institute, but the access is closed for fear of suicides, I remembered we recently had a similar discussion at our institute in Bucharest. Since some repair-work was being done in the terrace that is around the eighth floor, a proposal was made to use this opportunity to change it into a leisure area (some chairs, a table). But our director opposed it, and insisted that the door should remain locked, for fear of possible suicides.

I guess he was not thinking so much of our colleagues jumping from the terrace. Although there are a few weird characters, they don’t spend much time at the institute. And in the last twenty years all my colleagues have travelled a lot, so I presume they had plenty of opportunities to jump from much nicer places, if they really intended to do so. The director was mostly afraid of other peculiar inhabitants of Bucharest, who might see a high building and consider the opportunity rather tempting. When I recently told this to my son, he burst into laughter: it struck him as particularly preposterous to imagine a person choosing to end his or her life from the building of this prestigious institute of the Romanian Academy, and then presumably bribe the guards to get access to the eighth floor terrace. But one never knows.

The first case of suicide that I became aware of, indeed, used a terrace. L. was a nice, pretty girl that I had incidentally met several times in my twenties. At some point I even vaguely entertained the idea of a relationship, but somehow the opportunity did not arrive, and we never exchanged more than a few words. Then one day we heard that she had jumped from the tenth floor of a high building. It was quite a shock to everybody; suicides were not a common thing.

Later a couple of closer friends killed themselves this way – but the matter is controversial. They (a man who had emigrated to London, a woman who had returned to Bucharest from emigration) had more or less lost their minds; the cases were strikingly similar. So it was not clear whether they had really intended to jump over their respective balconies, or rather imagined that some small green men attacked them in the house, tried to escape outside, and fell accidentally.

But the story I intend to tell does not involve any balcony or terrace. It begins long ago, during our college years in Bucharest. That was of course a supremely exciting period of life, full of new freedoms, when teenager doubts are finally behind and the bounties of youth seem unlimited. It has left memories perduring after decades: the sound and color of endless meetings and parties, days and nights of talk, drink, smoke (no pot, though), dance, flirt and whatever.

David was usually there. A small, nice, red-haired guy, often staying inconspicuous in a corner of the room, smiling vaguely. Slightly stuttering, with a clumsy behavior, occasionally breaking a glass or putting his feet in a plate of sandwiches left on the floor. He did not dance, played bridge badly, did not excel in any other game; he was often unsuccessful in his efforts to enter conversations. But this didn’t seem to bother him: he was just happy to be there and a friend to everyone.

Not that he would take things for granted. He knew that friendship might be frail, that people are complicated and get easily vexed, or angry, or just uneasy; that relations often degrade. He was suffering when this happened, and felt somehow responsible for the well-being of his friends. Whenever he was aware of such an event, he would do all that he could to mediate, patch up, go from one another trying to arrange things. I think he imagined himself a kind of binder or glue for the groups that he was in (and there were plenty).

And he did not do this intrusively: he was a delicate and sensible person, always considerate about others’ feelings. He knew very well that people might feel pestered by his actions (some told him directly), and he would make allowance for this. But then he came back to his work: explaining misunderstandings and clarifying confusions was too important a task to be abandoned. Then, when things were finally arranged and relations were mended, he was happy to retreat in a corner of the room and enjoy.

It was not only about relations; he was always ready to help, in whatever sense. I remember a day on the beach when a newly arrived girl, anxious to go for the first swim, entered the sea without taking out her wristwatch. David noticed and run after her into the water, shouting; when she realized, she took off the wristwatch, almost without looking threw it back to him—they were both in one meter deep of water—and went on. He managed to catch it, and his heart was still pounding when he got back to us on the beach. But he was happy for having done two good deeds almost at once: first warning her, and then doing the catch. He liked telling the story afterwards.

To be honest, I cannot say that David’s dedication to friendship was much appreciated. For sure most of us would consider that their problems were none of his business, and nobody expressed gratitude for his interventions. But in the end we became accustomed to this behavior, and although we looked upon it ironically, we also tolerated it. That’s David, we would say, it’s like part of the decorum – a benign nuisance, after all…

Several years passed, and, predictably, things changed: less parties and gatherings, people were busy with jobs, got married, had children, etc. We did not have so much time for friends anymore. We saw less of David, and did not miss him; and he certainly felt it deeply. Also, there was not much satisfaction that he could find in his job, as an underpaid engineer somewhere in the outskirts of the town.

The beginning of the eighties were a bad time to be in Romania anyway; the main talk among my friends was if or when or how to leave the country: who did it, who will do it, and how fast there will be nobody left. (A popular joke said that the last who leaves should turn off the lights on the airport.) This was not a simple thing to do: one should either wait many years for permission, or decide no to return home from a rare excursion abroad (and thus abandon all belongings). But there were more favorable cases, in particular Jews: once they applied for emigration they got a positive answer in a few months. They were supposed to go to Israel, of course, but many of them went directly to western countries; or, if not directly, soon afterwards.

David was a Jew, and at some point, he also decided to leave. Naturally he would go to Israel and stay there. He was a deeply honest person, and I guess a similar sense of duty that he had previously shown towards his friends was now directed towards his new country. I do not think we had a formal farewell; but I remember two things about his departure: one is certainly true, the other maybe, maybe not.

The first involved a childhood friend who wanted to leave Romania. He offered her a formal marriage, which would allow them to emigrate jointly. The whole matter, of course, had to be quite secret, to avoid any suspicion of foul play: there were risks involved; but it went on smoothly. Of course she did not go to Israel at all, but headed directly to Germany; and David was happy that, once again, he had been able to help a friend.

The second may be apocryphal, but sounds plausible. The rumor was that before leaving Bucharest he sent a note to be published in a main journal in Israel, in the classified section: “D.E. announces his friends that he will land in Tel Aviv on… time… flight…” Apparently, none of the friends showed up.

We did not know much about David for a while; that was before internet, email, or facebook; news were heard occasionally, every now and then. Presumably he got a job and an apartment, learnt a new language, met new people. Israel was another planet, and details of life there were sparse. It was a nice surprise to learn a few years later that David is coming back for a visit. But when he arrived, we had an even bigger surprise: he did not come alone, and introduced us to his wife!

It is somehow strange that I do not remember any girlfriend of David during his years in Romania. There must have been some, but I assume his dedication to his friends had overshadowed completely any memory of a female companion (and surely there had not been male ones).

Lea was a rather impressive person, tall, good-looking, from many points of view the opposite of David. Straightforward and assertive, while he always had been complicated and slightly elusive. Even the appearance was strikingly different, his pale complexion and red hair contrasting with her dark skin and tresses. I guess she was also a few years younger. But they had the appearance of a happy couple; and David obviously was doubly proud: to present her to his friends, and to present his friends to her.

Although he was not much changed, there was something new that one could feel about David. As vacuous as these words are, he looked like having finally found a sense to his life. He had a place and a woman to which he belonged, and to which he could dedicate his altruism. His former restless behavior had been replaced by a restrained, calm composure. We joked that he had acquired some features of an old rabbi.

Not many of our emigrated friends did return to Romania, so it was quite an event, and we met several times during their stay. David seemed even to enjoy Bucharest, a town much gloomier than the time when he had left it: cars queueing for kilometers for gas, restaurants closing at 10pm, unlighted streets full of potholes. And then the people populating these streets: vague shadows dressed in gray, going silently their way, never smiling. But David did smile, often; and his mere presence made one feel better.

They came again to Romania a few years later, during a warm spring. By now the town was more friendly, bathed in honeysuckle and jasmine scents. We had many long evening walks together. My son was already a few years old, and he seemed to get on very well with them: he played hide and seek with Lea, and convinced David to carry him on his shoulders (it would not have worked with me). The last evening of their visit he fell asleep in my arms in the park; and we stayed late on a bench, till after midnight, talking a lot about a thousand things, old memories as well as plans for the future. They took the plane the next morning, going back to their bright life in that sunny country. Next time, we thought, they will bring also their kids.

The news came after a few months: David had hanged himself. Lea had left him after falling in love with an Arab colleague. Such things happen, of course; however, it was rather a shock to learn that all had actually happened before their last visit. But, since the voyage had been planned and announced some time in advance, she had accepted his request to act the happy couple for a week in Romania. No one among David’s closer relatives or friends managed to talk to her afterwards: she did not answer letters or phone calls. I guess one should not be surprised.

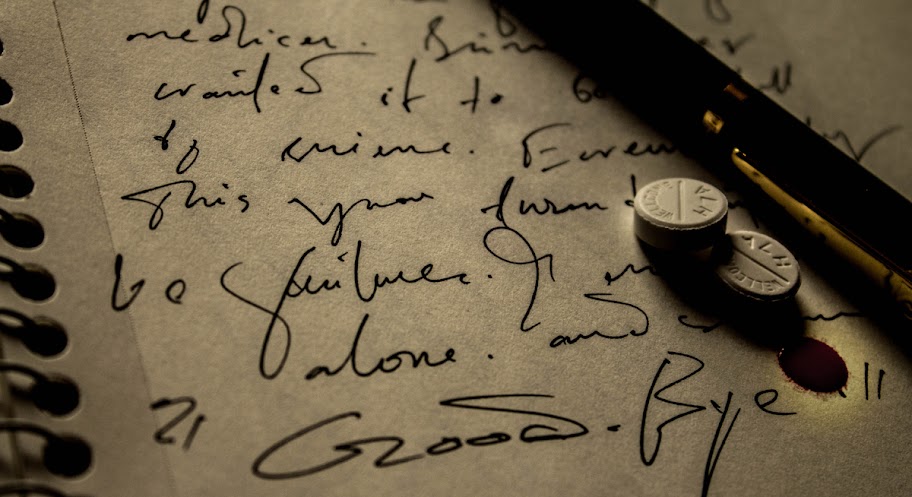

David did leave a suicide note. It only said that he bequeathed his body to the faculty of medicine, since he wanted it to be useful to science. Eventually, this also turned out to be a failure. He was living alone, so his body was found only after several days, when it could not be useful to science anymore.

*

Photography: Bijaya Datta

1 thought on “Suicide Notes”